The word “autism” (along with “schizophrenia”) was originally found in the writings of Swiss psychologist Paul Eugen Bleuler (CE1857-CE1939), in which he described the condition as involving a mental withdrawal into a private world and a poor tolerance for the encroachment of outside realities or conventions. These issues had been known to compromise (often severely) the autistic’s ability to communicate meaningfully with those outside the spectrum (allistics or “neurotypicals”—I put the latter in quotes as I’ve heard many apparent allistics tell me they don’t necessarily consider themselves “typical”), in many cases to the point of being functionally mute.

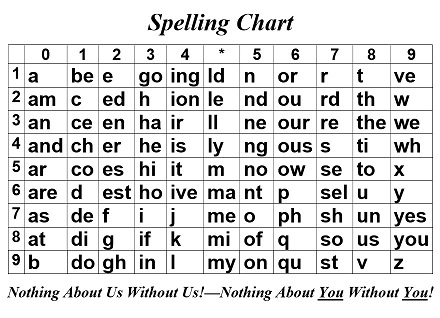

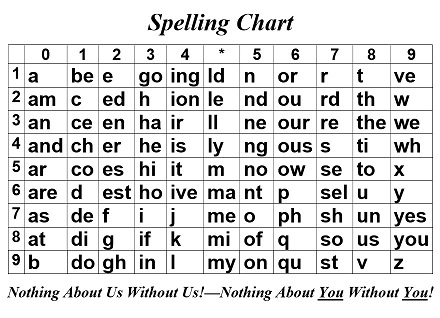

However, just because some people may not be able or inclined to engage in conventional conversation doesn’t necessarily mean that they cannot advocate for themselves or that any opinions they can communicate are any the less important. One of the most sterling counterexamples would have to be Indian spiritual leader Merwan Sheriar Irani, Sri Meher Baba (CE1894-CE1969). Even with the additional constraint of starting a “word fast” in CE1925, he was still able to communicate his teachings first via a slate, then an alphabet board and, by CE1954, a customised sign language. Yet for all that, he still made a substantial mark on society.

There are many, however, who would argue that Sri Baba’s “mutism” is not the same as the functional mutism of many autistics. In fact, it is more of a case of what I call situational mutism—the loss of, aversion to or convention precluding producing conventional oral speech depending on individual situation. Another (perhaps more common) example would be selective mutism, an anxiety disorder which prevents its victim from speaking in certain situations, especially when social response to such muteness all too often not only fails to mitigate, but in fact ends up compounding, the loss of language. Yet another form is character mutism, a common practice among mascots and similar performers who serve theme parks, sport teams and various other venues catering to children, such as hospitals.

In CE1505 the Sejm Walny (General Parliament) of the Kingdom of Poland formulated a constitution which they entitled Nihil Novi Nisi Commune Consensu (Latin for “nothing new without the common consent”), in which they loosely interpreted the title as nic o nas bez nas (Polish for “nothing about us without us”). This slogan would later be adopted by various, often marginalised, groups such as ethnic and special-needs subcommunities.

In some of the early history of autism self-advocacy, those in the more functional hues of the spectrum tended to be caught in a dilemma: those who were limited in using spoken language all too often would be second-guessed by the dominant allistic society before they could get out their spelling boards, while those who were solidly fluent were dismissed as charlatans or even renounced as greedy aggressors bent on crowding those more needful from their just due. In either case a sizable segment of the autism population was deprived of not only the supports they needed, but also of the opportunity to contribute to society (especially to the autism community) as a whole.

But if the more functional hues of the spectrum demand a voice, shouldn’t they have a commensurate responsibility to lend their ears to the advocates for the less functional? Infighting among the two extrema is a luxury which the autism community as a whole can ill afford. That was one of the principal reasons I felt led in early March 2017 to confess my emotional unease to an event mascot who held court at the neighbourhood shopping mall as well as explaining my condition to his co-host. I had hoped to catch a glimpse behind the curtain—not necessarily a glimpse of a modern-day Oscar Diggs (a very good man, mind you—just never any great shakes as a wizard), but an inkling of how Nothing About Us Without Us would look as Nothing About Them Without Them.